In my year-long challenge, I’ve been thinking of ways to make the intangible tangible. For example, what does contagion look like, or Black Lives Matter, or dignity, or death and immortality?

I’ve been thinking of death and immortality for a long time – what does it mean to die, in what ways are we immortal, how do we add meaning to this reality, what is our legacy?

Read infinitely, write finitely

The EEPROM memory of an ATtiny45 (my fave) has 256 addressable bytes. The EEPROM, for those who don’t know, is a place to store a byte that is retained after the chip turns off – so, say, you can store a value of something, put the chip to sleep, and then read the value when the chip wakes up.

But such power comes with a catch (as with all superpowers). While you can read from the EEPROM multiple times, there is a limit to how many times you can write to one of the 256 bytes. The manufacturer of the ATtiny45 says 100,000 times. Though there are reports that show the registers can actually write 1-2 million times (10-20x more than what the manufacturer says).

Of note, all the experiments I’ve seen seem to have stopped at the first failure of the chip. They were one-way, brute force read/write cycles until the first failure.

Lifelogging

I realized that killing an ATtiny45 EEPROM would be a way to explore death. Though I added a twist. I was going to observe it and record it and thus explore immortality, too.

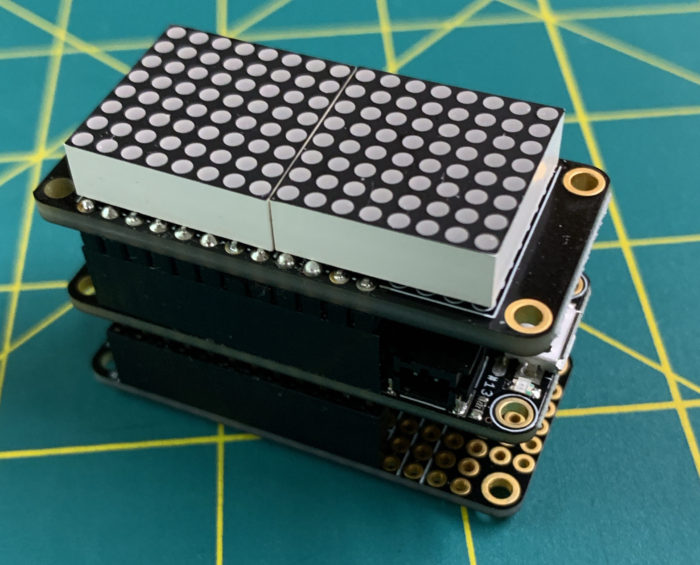

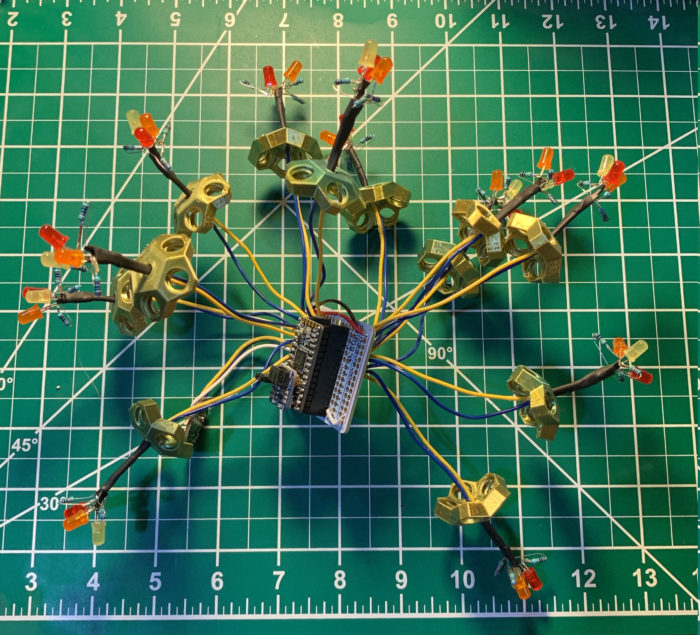

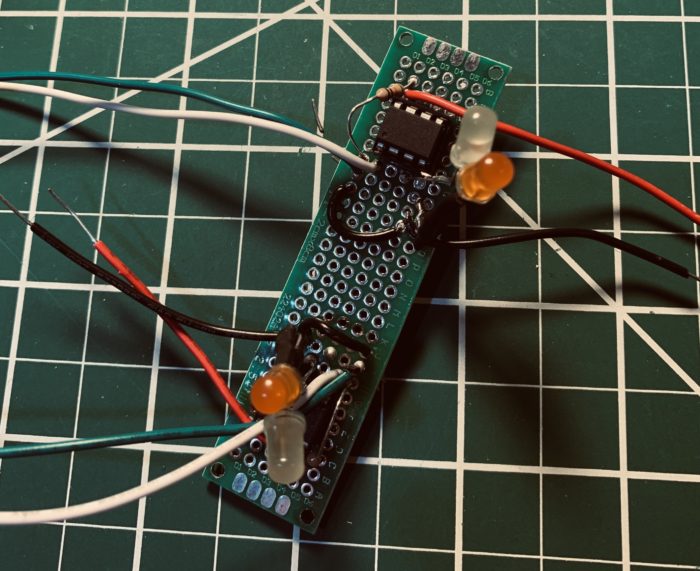

On the right is a stack I built to put this in an easy set up.

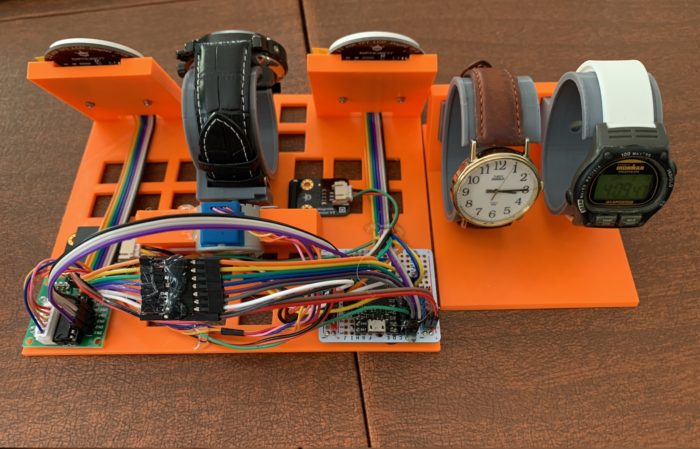

The bottom is a FeatherWing Proto with a DIP-8 socket for the ATtiny45 (yes, I want to do this a few times). The ATtiny45 is programmed to write a value to the EEPROM and then read the EEPROM, verifying the write*. The chip then sends the cycle, address, and pass/fail for every read over a serial connection to the main board.

For the main board, I currently have an Adafruit Feather M0 Adalogger (in the middle of the stack). The Adalogger will simply receive all the values the chip sends, plotting it on the 8×16 LED Matrix Featherwing (with a display clear at the start of each cycle), and logging the data to its SD card.

To simplify things, the chip does the failure testing. And I’ve decided to only read half the EEPROM (128 addresses) to match the 128 pixels on the matrix. Though, the Adalogger is only logging bad reads from the chip (or, if no failures, just the cycle – I still want to count the cycles). Logging only bad reads saves heaps of storage space.

Design choices

I know there are a zillion more efficient ways to do this. But this is the path I took. I had other design choices in mind: wanted to use CircuitPython (ended up using Arduino), wanted to use the main board to program the ATtiny right in the stack (not a separate programmer), wanted to be way more efficient where the computation happens (on the main board rather than the wee chip), wanted to use a faster (serial communication, chip speed, and storage writing) FeatherS2. Alas, I ran out of time and patience and ended up where I am (and that’s part of the reason of time-restricting these projects).

Where things are at

I hooked up the stack (added a battery for power continuity) and it’s been running a day or two (that’s the GIF above). I’m not so concerned about stopping and restarting, as the log files are numbered and I could stitch them together later.

I calculated how long to hit 100k cycles (about 20hrs – which has long passed) and 1M (8 days). While it seems from previous reports that I should only see something after 8 days, I want to answer a questions that I’ve never seen answered: if a write fails might it work on a subsequent read, or is the whole EEPROM dead, or just that address?

What I should see in my display (and data) is that an address will go dark – either to stay dark (single address fails once and always will fail) or will return (single address fails, but not always – still not usable, but not totally lost) or stops the whole process (when one address fails, all will fail).

Immortality

One other aspect I have yet to explore (as I haven’t killed a chip yet) is playing back the whole life of the chip. That is, when I’ve logged all the cycles until ALL the registers have failed, I can play back the chip’s life, indeed, its own particular life trajectory.

Question: when I play back the entirety of the chip’s life, is it dead and playback is just a memory, or is it the real thing? If I can play its life over and over again, is that immortality or just good record keeping? And what does that mean for our lives, our recorded selves, our digital contrails?

Dunno.

*Nerdy note: I actually used complementary values per read/write cycle to alternately flip all the bits of the byte – 240 (binary 11110000) and 15 (binary 00001111).